Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing, (23 June 1912–7 June 1954)

was an English mathematician, logician, and cryptographer. Alan Turing was based at Bletchley Park [2], Bletchley in Buckinghamshire, while acting as the leading cryptanalyst of German ciphers during the World War II. He was the central force in continuing to break the Enigma machine [3] [4] [5] [6] [7], and to crack the Lorenz cipher (codenamed "Tunny") [8].

Alan Turing was one of the pioneers of the information theory and computer science. He was highly influential in its development, giving a formalization of the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine, which can be considered a model of a general purpose computer [9].

Contents

Photos

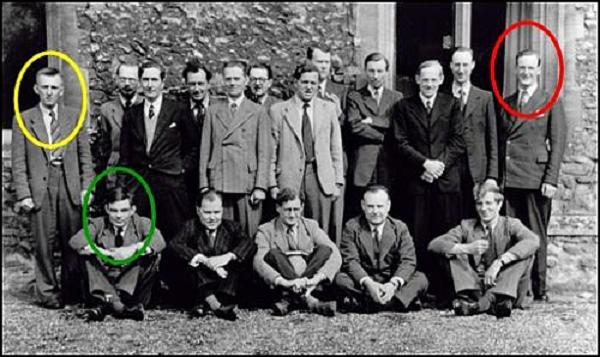

Ratio Club at Cambridge 1952, Giles Brindley (yellow), Donald MacKay (red), Alan Turing (green) [10]

Turing Machine

Turing machines are abstract symbol-manipulating devices which can be adapted to simulate the logic of any computer algorithm, described in 1936 by Alan Turing [11] , as thought experiment about the limits of mechanical computation. An example of a concrete Turing machine is the Busy beaver [12].

The Universal Turing machine can simulate an arbitrary Turing machine on arbitrary input, and can be considered as the origin of the John von Neumann architecture. A universal Turing machine can calculate any recursive function, decide any recursive language, and accept any recursively enumerable language. According to the Church-Turing thesis, the problems solvable by a universal Turing machine are exactly those problems solvable by an algorithm or an effective method of computation, for any reasonable definition of those terms. For these reasons a system that can simulate a universal Turing machine is called Turing complete.

Turing Test

Turing addressed the problem of artificial intelligence, and proposed an experiment now known as the Turing test, an attempt to define a standard for a machine to be called "intelligent" [13] [14] .

Chess and Go

Alan Turing used chess-playing as an example of what a computer could do. Along with David Champernowne he specified a chess playing algorithm, implemented as "paper machine" dubbed Turochamp. Since there was no machine yet that could execute the instructions, he did himself, acting as a human CPU requiring more than half an hour per move. One game is recorded, which Turing's "paper machine" lost to one of his colleagues [15], Alick Glennie. At the University of Manchester, Turing began programming Turochamp, as well as Michie's and Wylie's program Machiavelli, to run on a Ferranti Mark 1 computer, but could not complete them [16].

Could one make a machine?

In his 1953 paper 'Chess' in Bowden's Faster Than Thought [17] , Turing asks some questions, answered and discussed them, mentioning evaluation features, the concepts of minimax strategy, variable look-ahead, quiescence and learning. He does not explicitly mention the name Turochamp, but the 'Machine', and its game versus a human [18] [19] .

When one is asked 'Could one make a machine to play chess?', there are several possible meanings which might be given to the words. Here are a few:

- Could one make a machine which would obey the rules of chess, i.e. one which would play random legal moves, or which could tell one whether a given move is a legal one?

- Could one make a machine which would solve chess problems, e.g. tell one whether, in a given position, white has a forced mate in three?

- Could one make a machine which would play a reasonable good game of chess, i.e. which, confronted with an ordinary (that i, not particularly unusual) chess position, would after two or three minutes of calculation, indicate a passably good legal move?

- Could one make a machine to play chess, and to improve its play, game by game, profiting from its experience?

To these we may add two further questions, unconnected with chess, which are likely to be on the tip of the reader's tongue.

- Could one make a machine which would answer questions put to it, in such a way that it would not be possible to distinguish its answers from those of a man?

- Could one make a machine which would have feelings like you and I do?

Andrew Hodges

Andrew Hodges in the Alan Turing Scrapbook - the Origins of Artificial Intelligence [20] :

Alan Turing talked at Bletchley Park with his younger colleague Jack Good about what we would now call chess-playing programs. They got the idea of searching decision trees for the best move.

Turing knew the game of Go as early as 1936: in fact he explained it to Christopher Morcom's mother shortly before he left for America. At Bletchley Park he showed the game to others including Jack Good. According to the British Go Association's page it was Good who twenty years later popularised the game in Britain.

In the later years of the war, he talked with a young student, Donald Michie, about the prospect of machines 'learning.' In other conversations he talked about 'building a brain.' It seems that it was during the war that he came to the view that anything done by the brain must be a computable operation, and so could be simulated by a Turing machine.

Turing's post-war ideas reflected the discussions he had enjoyed during the wartime period. After 1945 he often used chess-playing as an example of what a computer could do, and in his 1946 report on the possibilities of a computer, made his first reference to machine 'intelligence' in connection with chess-playing. In 1948 he met Donald Michie again and competed with him in writing a simple chess-playing algorithm.

Jack Good

In letters to Turing, on September 16 and October 3, 1948, I mentioned the idea of resonance circuits in the brain; especially as a method for noticing analogies... In the postscript I discussed chess-playing machines, which he and I had discussed in 1941, and gave a reasonable definition of a forced variation. I took for granted the need to distinguish between quiescent and non-quiescent positions. Shannon's paper on chess appeared in 1950.

Punishment and Death

Turing was just 41 years old when he committed suicide, two years after undergoing a court-ordered chemical castration. He had been found guilty of gross indecency for having a homosexual relationship. The punishment in 1952 was either a prison sentence or chemical castration. Turing chose the latter. In September 2009 the British government has issued a formal apology for the way Alan Turning was treated [22] [23] .

See also

- Alan Turing webcast from Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum

- David Champernowne

- Ferranti Mark 1

- History of Computer Chess

- Konrad Zuse

- Turochamp

Selected Publications

1936 ...

- Alan Turing (1936). On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem. pdf

1940 ...

- Alan Turing (1949). Alan Turing's Manual for the Ferranti Mk. I. transcribed in 2000 by Robert Thau, pdf from The Computer History Museum

1950 ...

- Alan Turing (1950). Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind, 59, 433-460. pdf from The Computer History Museum

- Alan Turing (1951). Programmers' Handbook for the Manchester Electronic Computer Mark II. 1st edition

- Alan Turing (1952). Programmers' Handbook for the Manchester Electronic Computer Mark II. 2nd edition, revised by R.A. Brooker [25]

- Alan Turing (1953). Chess. part of the collection Digital Computers Applied to Games. in Bertram Vivian Bowden (editor), Faster Than Thought, a symposium on digital computing machines, reprinted 1988 in Computer Chess Compendium, reprinted 2004 in Chapter 16 of The Essential Turing ... [26]

1990 ...

- Edward Feigenbaum (1996). How the “What“ Becomes the “How“. Communications of the ACM, Vol. 39, No. 5, pdf hosted by The Computer History Museum

2000 ...

- Jack Good (2000). Turing’s anticipation of emprical Bayes in connection with the cryptanalysis of the naval enigma. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation, Vol. 66, No. 2 [27] [28] [29]

- Alan Turing, B. Jack Copeland (editor) (2004). The Essential Turing, Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma. Oxford University Press, amazon, google books

2010 ...

- B. Jack Copeland, Diane Proudfoot (2011-2012). Turing, Father of the Modern Computer. The Rutherford Journal - The New Zealand Journal for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, Vol. 4 » with photos of Alan Turing, John von Neumann, Dietrich Prinz, Christopher Strachey, Jack Good, Arthur Samuel, Herbert Simon, Allen Newell, ...

- Andrew Appel (ed.) (2012). Alan Turing's Systems of Logic: The Princeton Thesis. Princeton University Press

- Christos H. Papadimitriou, Leonard Adleman, Richard Karp, Donald Knuth, Robert E. Tarjan, Leslie Valiant (2012). An Algorithmic View of the Universe. ACM-Turing 2012

- Guy McCrossan Haworth (2013). Turing, Kasparov and the Future. ICGA Journal, Vol. 36, No. 1 » Turochamp

- S. Barry Cooper, Jan van Leeuwen (2013). Alan Turing: His Work and Impact. Elsevier Science

- David Levy (2013). Alan Turing on Computer Chess. pp. 644-650

- Andrew Hodges (2014). Alan Turing: The Enigma. Vintage Random House, Princeton University Press

- Kieran Greer (2014). Turing: Then, Now and Still Key. arXiv:1403.2541

- Stephen Muggleton (2014). Alan Turing and the development of Artificial Intelligence. AI Communications, Vol. 27, No. 1, pdf

Forum Posts

- How did Alan Turing's program work? by Pete Galati, CCC, April 20, 2000

- Finally Science Meets Computer Chess XI (Turing) by Phil Innes, rgcc, November 11, 2001

External Links

- Alan Turing from Wikipedia

- Alan Turing - Wikiquote

- Turing Award from Wikipedia by the ACM

- National Portrait Gallery - Portrait - NPG x27078; Alan Mathison Turing by Elliott & Fry

- The Mind and the Computing Machine edited by B. Jack Copeland, from The Rutherford Journal - The New Zealand Journal for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology

- Alan Turing by Jürgen Schmidhuber

- Turing letter to W. Ross Ashby from William Ross Ashby's Digital Archive

- Computer und Schach: "Die goldene Gans, die niemals schnattert" by André Schulz, Spiegel Online, November 12, 2003 (German) [30]

- Alan Turing by André Schulz, June 07, 2004, ChessBase Nachrichten (German)

- Alan Turing: "I am building a brain." Half a century later, its successor beat Kasparov by S. Barry Cooper, The Northerner | UK news, guardian.co.uk

- Alan Turing: why the tech world's hero should be a household name by Vint Cerf, BBC News, June 18, 2012

- Alan Turing: Inquest's suicide verdict 'not supportable' by Roland Pease, BBC News, June 23, 2012

- Spies and Spymasters > Second World War > Alan Turing from Spartacus Educational

- Chess and the Code-Breakers by Edward Winter

Turing Machine

- Turing machine from Wikipedia

- Universal Turing machine from Wikipedia

- Church-Turing thesis

- Turing completeness from Wikipedia

Devices and Computers

Turing Test

Turing Archive

- AlanTuring.net - The Turing Archive for the History of Computing

- Early AI Programs from AlanTuring.net by B. Jack Copeland

Andrew Hodges

- Alan Turing: Primary Sources, notes by Andrew Hodges, author of Alan Turing: the Enigma

- Alan Turing - Home Page maintained by Andrew Hodges, author of Alan Turing: the Enigma

- The Alan Turing Internet Scrapbook maintained by Andrew Hodges, author of Alan Turing: the Enigma

Literature

- Books on Alan Turing from amazon.com

- Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma

- Christof Teuscher - My Books on Alan Turing

Turing Year 2012

- Alan Turing Year from Wikipedia

- The Alan Turing Year - 2012 Turing Centenary

- Eminent & enigmatic - 10 aspects of Alan Turing, the Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum

- Turing Jahr 2012 - Alan Turing Year 2012, Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V (German)

- Donald Knuth in Alan Turing Year from I Programmer - programming, reviews and projects, January 10, 2012 » Donald Knuth

- Alan Turing Year (alanturingyear) at Twitter

- ACM A.M. Turing Centenary Celebration

- The Alan Turing Centenary Conference Manchester UK, June 22-25, 2012, hosted by the University in Manchester

Movies

- featuring Marvin Minsky, Andrew Hodges, Norman Routledge, Jack Good, Shaun Wylie, Joan Clarke, Robin Gandy et al.

References

- ↑ Alan Turing from Wikipedia

- ↑ Bletchley Park Museum

- ↑ The plugboard-equipped Enigma machine was already solved in 1932 by Marian Rejewski at Biuro Szyfrów, the Polish General Staff's agency, ongoing development of methods and equipment to exploit Enigma decryption was continued before and during World War II by Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski

- ↑ Marian Rejewski (1981). How Polish Mathematicians Deciphered the Enigma. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, pdf

- ↑ Polish Enigma double from Wikipedia

- ↑ Alan Turing - Cryptanalysis from Wikipedia

- ↑ Cryptanalysis of the Enigma from Wikipedia

- ↑ Jack Good, Donald Michie, Geoffrey Timms (1945). General Report on Tunny from The Turing Archive for the History of Computing

- ↑ Alan Turing from Wikipedia

- ↑ noos anakainisis: The Ratio Club, September 17, 2010

- ↑ Alan Turing (1936). On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem.

- ↑ Busy Beaver by Heiner Marxen

- ↑ Alan Turing (1950). Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind, 59, 433-460. pdf from The Computer History Museum

- ↑ James H. Moor (2003). The Turing Test: The Elusive Standard of Artificial Intelligence. Kluwer Academic Publishers

- ↑ A short history of computer chess from ChessBase

- ↑ Chronology of Computing compiled by David Singmaster

- ↑ Alan Turing (1953). Chess. part of the collection Digital Computers Applied to Games. in Bertram Vivian Bowden (editor), Faster Than Thought, a symposium on digital computing machines, reprinted 1988 in Computer Chess Compendium, reprinted 2004 in Chapter 16 of Alan Turing, B. Jack Copeland (editor) (2004). The Essential Turing, Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma. Oxford University Press, amazon, google books

- ↑ Anmerkungen zur Programmierung der Turing-Engine by Mathias Feist, ChessBase Spotlights (German, with original article 'Chess' by Alan Turing)

- ↑ Re: How did Alan Turing's program work? by Frederic Friedel, CCC, April 22, 2000

- ↑ Alan Turing Scrapbook - the Origins of Artificial Intelligence by Andrew Hodges

- ↑ Excerpts from Acceptance Speech for the 1998 Computer Pioneers Award from the IEEE - Jack Good hosted by Atlas Computer Laboratory

- ↑ Thousands call for Turing apology, BBC NEWS August 31, 2009

- ↑ Treatment of Alan Turing was “appalling” - PM, Gordon Brown’s statement from Number10.gov.uk, September 10, 2009

- ↑ Janus: The Papers of Alan Mathison Turing

- ↑ Mark 1 Documents from Computer 50 - The University of Manchester Celebrates the Birth of the Modern Computer

- ↑ Anmerkungen zur Programmierung der Turing-Engine by Mathias Feist, ChessBase Spotlights (German, with original article 'Chess' by Alan Turing)

- ↑ Banburismus from Wikipedia

- ↑ Good–Turing frequency estimation from Wikipedia

- ↑ David McAllester, Robert Schapire (2000). On the Convergence Rate of Good-Turing Estimators. COLT 2000, CiteSeerX

- ↑ New Chessbase Engine called "Turing" by Ingo Bauer, CCC, November 12, 2003