Herbert Simon

Herbert Alexander Simon, (June 15, 1916 – February 9, 2001)

was an American scientist and artificial intelligence pioneer, economist, psychologist, and professor, most notably, at Carnegie Mellon University, which became an important center of AI and computer chess, associated with names like Hans Berliner, Carl Ebeling, Feng-hsiung Hsu, Murray Campbell and the computers HiTech and Deep Thought. Herbert Simon received many top-level honors, most notably the Turing Award (with Allen Newell) (1975) for his AI-contributions [2] and the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for his pioneering research into the decision-making process within economic organizations (1978) [3].

Contents

Photos

In the late 1950s, Carnegie Mellon University researchers Allen Newell (r) and Herbert Simon (l),

together with Cliff Shaw (not shown) at the RAND Corporation, were early pioneers in the field of

artificial intelligence and chess software. The NSS program ran on the Johnniac computer ... [4]

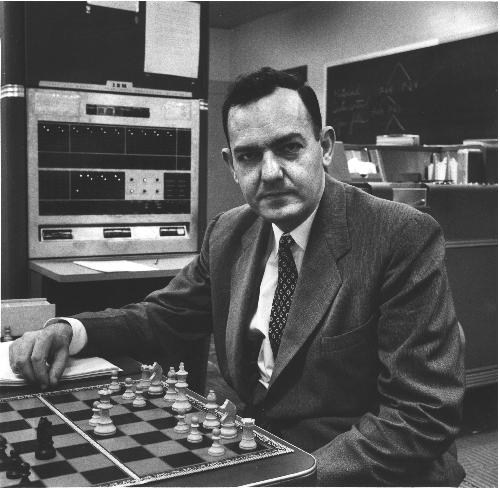

Herbert Simon [5]

NSS

In the late 50s, Allen Newell, Cliff Shaw, and Herbert Simon developed the chess program NSS. It was written in a high-level language. With Allen Newell, Herbert Simon was inventor of the alpha-beta algorithm - which was independently invented by John McCarthy, Arthur Samuel and Alexander Brudno. In 1957 Herbert Simon said that within 10 years, a digital computer would be the world's chess champion [6].

Quotes

John McCarthy

Quote by John McCarthy from Human-Level AI is harder than it seemed in 1955 on the Dartmouth workshop:

Chess programs catch some of the human chess playing abilities but rely on the limited effective branching of the chess move tree. The ideas that work for chess are inadequate for go. Alpha-beta pruning characterizes human play, but it wasn't noticed by early chess programmers - Turing, Shannon, Pasta and Ulam, and Bernstein. We humans are not very good at identifying the heuristics we ourselves use. Approximations to alpha-beta used by Samuel, Newell and Simon, McCarthy. Proved equivalent to minimax by Hart and Levin, independently by Brudno. Knuth gives details.

Hans Berliner

Hans Berliner in A Life's Appraisal [7] :

Herbert Simon thought of himself as a Renaissance man. He was involved in many enterprises, and had a knack for appearing at or near the top in most of them. In 1978, he received a Nobel Prize in economics for nearly forgotten work he had done decades before, and he slept in unheated barracks in China and learned to read Chinese in order to acquaint himself with the Mainland way of doing things while offering what he could.

His detractors would say he dabbled a great deal, could always be counted on to be there at the finish line, could provide a reprint of any of the thousands of papers he had ever written at a moment's notice, and was arrogant in a very refined kind of way.

For me, Herb Simon was the guy who in 1956 at his inaugural address as President of the Operations Research Society of America predicted that within 10 years a computer would be World Chess Champion unless it were barred from the competition. I had seen the articles on the Rand Corp. chess program authored by Newell, Simon, and Shaw that this prediction was based upon, and I laughed, because I knew too much about chess, and did not see anything resembling the kind of play that was required to even play at the Master level. Here again was a situation typical of Herb's career. Many looked in wonder, and many looked with disdain. To make such a prediction was not a very scientific thing to do. The program had never played a tournament game. Even when playing against people who were touted as being champions of something-or-another it showed rather serious weaknesses. But Herb always liked being there first.

In later years when I discussed this prediction with him (he vehemently rooted for computers ever after, even if, as DEEP BLUE, they did not play chess in the style of Cognitive Psychology), he always said that it was important for science to make such predictions as they galvanized the field toward certain important goals. And he would point out DaVinci's drawings of man flight, and other things. To him it was important to push the ball along, and just how scientific it was, could be left for future appraisals. Yet Herb was one of the first members of the National Academy of Science to come from the ranks of the soft sciences rather than from Engineering, Physics and Chemistry. As such he opened the door for things that this nation (US) sorely needed to examine.

I first met Herb at a meeting in 1967, where he was an invited speaker. I chatted with him after his presentation, and was surprised to find that he knew who I was. I indicated that after the formidable work of Greenblatt, I had been encouraged to try to write a chess program on my own time at IBM, where I was then employed. He was very interested, and when I mentioned that I did not intend to stay at IBM too much longer, he was quick to suggest that I should visit Carnegie-Mellon University and see what they had to offer there. In due course I did visit, and in 1969 entered there as a first-year graduate student in Computer Science. He was on my committee when I did my thesis which demonstrated how a computer could do very complicated analytical things in the Human Style. But typical of Herb, he was not involved in the nuts and bolts, and the main credit for my guidance must be given to Allen Newell.

While a graduate student at CMU, I had ample opportunity of interact with Herb and Bill Chase who was a Post-Doc and later a professor in the Psychology Department there. It was there that I got involved in the Human Perception of chess which built on the work of the Russians in the 1930s and of De Groot in the 1940s. I was very impressed by the machinery that clearly existed in the human head and made it possible to remember positions almost perfectly even after having seen them for only 2 seconds. What was even more interesting, was that errors in reconstructing the position had a definite pattern to them. For instance, a Bishop may be misplaced in the reconstruction, but it would still be on the critical diagonal, and thus retain its function on that diagonal whatever the function was. This insight has been incredibly important in my career, and is seen clearly in the program CAPS, in my book The System, and in other writings presently under way.

Herb was excellent in pointing these things out and in developing the interpretation that allowed further progress into insights of what our brain machine was really doing. For me, it was very exciting to watch and wonder. Of course, what was missing at that time was a method of emulating human learning without which we would be faced with infinite twiddling of data by a human being who could just not grasp the complexity of all he was twiddling. Thus, until neural net learning came along, there was really no hope of building a program that could play in the human style. Yet, without people such as Herb, it is likely that no one would have tried. Now, with the success of the brute force method, it is doubtful anyone will ever try it. The fact that neural nets can be the difference is documented by the success of Tesauro's backgammon program that learned strategies that almost no one new, and became a top player by playing millions of games against itself. To do that in chess would have been much harder, but humans were doing it.

Herb Simon's role in all this is not at all clear. He was always there to discuss things with genuine interest, and had an amazing repetoire of facts that could be pertinent of the situation. One would come away from such a session with months of research leads to chase down. Not too many people could have done that. I will miss you, Herb.

George W. Baylor

George W. Baylor's Remembrance on Herbert A. Simon [8] :

Herb Simon has been such a towering influence and determining force in my life that it is hard to imagine what my life would have been like without him. It was in 1959-60, as a sophomore at Carnegie Institute of Technology, that I first met "Dr. Simon." I mainly played chess, but he and Allen Newell, were programming computers to play chess. I believe we played some games together and I beat him. He said that my "program" was better than his. Then he hired me as a summer research assistant to work on chess machines! A year or two later he sent me to Amsterdam to help translate Adriaan de Groot's book on the thought processes of the chess player. When I returned, he directed my master's thesis on a mating combinations program, which he had already begun with his son, Pete. Like a clever father, he subtly transformed me from an aspiring chess professional - though, more likely, impoverished chess bum - into a cognitive psychologist. He also directed my doctoral dissertation, a computer simulation of some visual mental imagery tasks, though I knew he would have preferred me to continue working on chess. He was stuck with his prediction that a computer would beat the world chess champion within ten years - it took 40. But sons must differentiate themselves from their fathers, mustn't they?

By then it was 1967-68 and the war in Vietnam was still raging. I went to Canada. Though Simon's views on the war were much less clear-cut than my own, he supported me. He even said that I could defend my thesis by teleconference. Though that proved unnecessary, you can imagine how much that meant to me. We continued to correspond and occasionally saw each other, but our lives diverged, as lives do.

Thirty years later, in 1997-98, I returned to Carnegie-Mellon University to do a sabbatical with Herb. It was as though I was his graduate student all over again: I presented my research problems and he helped me solve them; he presented his research and I struggled to understand it. I never really overcame my fear of his staggering intellect, but it mattered less because the love between us was so palpable. This was also the time when he had his major heart operation, and I felt privileged to be near him and Dorothea. He told me a dream he had while in the hospital, and I was thrilled to be able to offer an interpretation - my turn to give. I am so grateful for those months in Pittsburgh. Thank you, Herb. I am so grateful for the decade at C. I. T.: Thank you, Dr. Simon. It is hard to imagine a world without you. May you rest in peace.

Fernand Gobet

Fernand Gobet's Remembrance on Herbert A. Simon [9] :

"What new data do we have about chess today?" Herb would often ask at the beginning of our almost weekly meetings, which lasted from 1990 to 1995. He was immensely curious to learn about new phenomena, and had an obvious pleasure to analyse data, always looking for hidden patterns and better representations; as many of us have learned, Herb was outstanding at making sense out of complex data sets.

Herb’s curiosity was always present in our meetings, well beyond scientific data. For example, he had a passion for learning and improving his knowledge of foreign languages (he had translated scientific work from Russian and Dutch, and probably from other languages as well). When he volunteered to read the draft of my thesis in French, I expressed my worries about the time it would take. He reassured me: "Your French is much easier to read than Proust’s."

Herb was also very generous with his students and colleagues. When some arcane immigration regulation allowed me to be employed by Carnegie Mellon University, but not to be paid, Herb did not hesitate to support me financially for a couple of months.

Meetings with him were alternatively dense and relaxed, focused and wide-ranging. His informal style made you sometimes forget that you were talking to one of the greatest scholars and one of the last true humanists of the 20th century. While open to new ideas, he also had little patience for bad ideas. However, even then, he managed to refute them in a way that didn’t make you feel too bad.

He was exigent and expected his collaborators to share his passion for work. But of course, the results were highly rewarding. In a very elegant and efficient way, he taught many of us much about science, and mainly that scientific research can be an exciting voyage of discovery.

Chess Projects

See also

- Cognition

- History of Alpha-Beta

- History of Computer Chess

- Perception in Chess

- Perception - Video

- Psychology

- Kasparov versus Deep Thought 1989 documentary

Autobiography

- Herbert A. Simon (1991). Models of my Life. Basic Books, New York, N.Y.

- A Remarkable Autobiography of the Nobel Prize Winning Social Scientist and Father of Artificial Intelligence.

Selected Publications

1956 ...

- Allen Newell, Herbert Simon (1956). The logic theory machine-A complex information processing system. IRE Transactions on Information Theory, Vol. 2, No. 3

- Allen Newell, Cliff Shaw, Herbert Simon (1958). Chess Playing Programs and the Problem of Complexity. IBM Journal of Research and Development, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 320-335. Reprinted (1963) in Computers and Thought (eds. Edward Feigenbaum and Julian Feldman), pp. 39-70. McGraw-Hill, New York, N.Y. pdf

- Allen Newell, Cliff Shaw, Herbert Simon (1959). Report on a general problem-solving program. Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Processing, pp. 256-264 [15]

1960 ...

- Edward Feigenbaum, Herbert Simon (1961). Performance of a Reading Task by an Elementary Perceiving and Memorizing Program. RAND Paper, pdf

- Edward Feigenbaum, Herbert Simon (1961). Forgetting in an association memory. ACM '61, pdf

- Edward Feigenbaum, Herbert Simon (1962). A Theory of the Serial Position Effect. British Journal of Psychology, Vol. 53, 307-32, pdf

- Herbert A. Simon, Peter A. Simon (1962). Trial and Error Search in Solving Difficult Problems: Evidence from the Game of Chess. Behavioral Science, Vol. 7, No. 4

- Edward Feigenbaum, Herbert Simon (1963). Elementary Perceiver and Memorizer: Review of Experiments. in Symposium on Simulation Models

- Herbert Simon, Edward Feigenbaum (1964). An Information-processing Theory of Some Effects of Similarity, Familiarization, and Meaningfulness in Verbal Learning. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, Vol. 3, No. 5, pdf

- Allen Newell, Herbert Simon (1965). An Example of Human Chess Play in Light of Chess Playing Programs. In Norbert Wiener, J. P. Schadé (eds.) Progress in Biocybernetics. Vol. 2, Elsevier

- George W. Baylor, Herbert A. Simon (1966). A chess mating combinations program. AFIPS Joint Computer Conferences, reprinted in Herbert A. Simon (1979). Models of Thought. Yale University Press, pp. 181-200, in David Levy (ed.) (1988). Computer Chess Compendium.

- Herbert Simon, Michael Barenfeld (1968). Information Processing in the Perception of Chess Positions. Carnegie Mellon University, Paper #127

- Herbert Simon (1969). The Sciences of the Artificial. MIT Press, 1st Edition

- Herbert Simon, Michael Barenfeld (1969). Information-processing analysis of perceptual processes in problem solving. Psychological Review, Vol. 76, No. 5, pdf, reprinted in Herbert A. Simon (1979). Models of Thought. Yale University Press, pdf

1970 ...

- Allen Newell, Herbert Simon (1972). Human Problem Solving. Prentice-Hall

- Herbert Simon, Laurent Siklóssy (eds.) (1972). Representation and Meaning: Experiments with Information Processing Systems. Prentice-Hall

- Herbert Simon (1973). Lessons from Perception for Chess-Playing Programs (and Vice Versa). Computer Science Research Review 1972-73, pdf

- William Chase, Herbert Simon (1973). The Mind’s Eye in Chess. Visual Information Processing: Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Carnegie Psychology Symposium (ed. W. G. Chase), pp. 215-281. Academic Press, New York. Reprinted (1988) in Readings in Cognitive Science (ed. A.M. Collins). Morgan Kaufmann, San Mateo, CA.

- William Chase, Herbert Simon (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 4, No. 1, pdf [18]

- Herbert Simon, William Chase (1973). Skill in Chess. American Scientist, Vol. 61, No. 4, Reprinted (1988) in Computer Chess Compendium, pdf

- Herbert Simon, Kevin J. Gilmartin (1973). A Simulation of Memory for Chess Positions. Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 5, No. 1, reprinted in Herbert Simon (1979). Models of Thought, Yale University Press

- Herbert Simon (1974). How big is a chunk? Science, Vol. 183, pdf

- Allen Newell, Herbert Simon (1976). Computer Science as Empirical Inquiry: Symbols and Search. Communications of the ACM, Vol. 19, No. 3, ACM Turing Award Lecture, pdf from The Computer History Museum [19]

- Herbert A. Simon (1979). Models of Thought. Yale University Press

1980 ...

- Herbert Simon (1980). Cognitive Science: The Newest Science of the Artificial. Cognitive Science, Vol. 4, No. 1

- Herbert Simon (1981). Prometheus or Pandora: The Influence of Automation on Society. IEEE Computer, Vol. 14, No. 11

- Herbert Simon (1983). Search and Reasoning in Problem Solving. Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 21, Nos 1-2

- Edward Feigenbaum, Herbert Simon (1984). EPAMlike models of recognition and learning. Cognitive Science, Vol. 8, 305-336, pdf

- Herbert Simon (1985). Obituary: William G. Chase (1940–1983). American Psychologist, Vol. 40, No. 5 » William Chase

- Herbert Simon (1986). Whether Software Engineering Needs to Be Artificially Intelligent. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, Vol. 12, No. 7

- Herbert Simon (1988). Prospects for Cognitive Science. FGCS 1988

1990 ...

- Herbert Simon (1991). Artificial Intelligence: Where Has It Been, Where is it Going? IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, Vol. 3, No. 2

- Herbert A. Simon (1991). Models of my Life. Basic Books, New York, N.Y.

- Herbert Simon, Jonathan Schaeffer (1992). The Game of Chess. in Handbook of Game Theory with Economic applications (eds. Robert J. Aumann and Sergiu Hart). North Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. ISBN-13: 978-0-444-88098-7, ps

- Herbert Simon (1995). Explaining the Ineffable: AI on the Topics of Intuition, Insight and Inspiration. IJCAI 1995, pdf

- Herbert Simon (1995). Artificial Intelligence: An Empirical Science. Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 77, No. 1

- Howard B. Richman, James J. Staszewski, Herbert Simon (1995). Simulation of Expert Memory with EPAM IV. Psychological Review, Vol. 102

- Howard B. Richman, Fernand Gobet, James J. Staszewski, Herbert Simon (1995). Perceptual and Memory Processes in the Acquisition of Expert Performance: The EPAM Model. Complex Information Processing, Working Paper #528

- Fernand Gobet, Herbert Simon (1996). Templates in Chess Memory: A Mechanism for Recalling Several Boards. Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 31, pp. 1-40.

- Fernand Gobet, Herbert Simon (1996). Recall of random and distorted positions: Implications for the theory of expertise. Memory & Cognition, 24, 493-503.

- Fernand Gobet, Herbert Simon (1996). Recall of rapidly presented random chess positions is a function of skill. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3, 159-163, word reprint

- Herbert Simon (1996). The Sciences of the Artificial. MIT Press, 3rd Edition 1996, amazon

- Fernand Gobet, Howard B. Richman, James J. Staszewski, Herbert Simon (1997). Goals, Representations, and Strategies in a Concept Attainment Task: The EPAM model. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, Vol. 37, pdf

- Yasser Seirawan, Herbert Simon, Toshinori Munakata (1997). The Implications of Kasparov vs. Deep Blue. Communications of the ACM, Vol. 40, No. 8, pdf hosted from The Computer History Museum

- Fernand Gobet, Herbert Simon (1998). Expert chess memory: Revisiting the chunking hypothesis. Memory, 6, 225-255

- Fernand Gobet, Herbert Simon (1998). Pattern recognition makes search possible: Comments on Holding (1992). Psychological Research, Vol. 61, pdf [22]

2000 ...

- Fernand Gobet, Herbert Simon (2000). Five Seconds or Sixty? Presentation Time in Expert Memory. Cognitive Science, Vol. 24, No. 4

- Hans Berliner (2001). HERBERT A. SIMON (1916-2001): A LIFE'S APPRAISAL, ICCA Journal, Vol. 24, No. 1

- Fernand Gobet (2001). HERBERT A. SIMON (1916 - 2001): THE SCIENTIST OF THE ARTIFICIAL. ICCA Journal, Vol. 24, No. 1

- Subrata Dasgupta (2003). Multidisciplinary creativity: the case of Herbert A. Simon. Cognitive Science, Vol. 27, No. 5

- Pamela McCorduck (2004). Machines Who Think: A Personal Inquiry into the History and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence. A. K. Peters (25th anniversary edition)

External Links

- Herbert A. Simon from Wikipedia

- Herbert A. Simon - Biographical

- Herbert A. Simon - A.M. Turing Award Winner

- Computer Science as Empirical Inquiry: Symbols and Search (pdf) by Allen Newell and Herbert Simon, 1975 ACM Turing Award Lecture

- The Mathematics Genealogy Project - Herbert Simon

- Herbert A. Simon: A Family Memory

- Herbert Simon Collection (Carnegie Mellon Libraries)

- Herbert A. Simon Tribute

References

- ↑ Herbert Simon Collection - Contents [Carnegie Mellon Libraries]

- ↑ Herbert A. Simon - A.M. Turing Award Winner

- ↑ Herbert A. Simon - Biographical

- ↑ Aritificial Intelligence pioneers Allen Newell (right) and Herbert Simon 1958 Courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University, The Computer History Museum

- ↑ Herbert Simon 1958 ca. Courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University, The Computer History Museum

- ↑ Computer Chess History by Bill Wall

- ↑ Hans Berliner (2001). HERBERT A. SIMON (1916-2001): A LIFE'S APPRAISAL, ICCA Journal, Vol. 24, No. 1

- ↑ All Remembrance of Herbert A. Simon

- ↑ All Remembrance of Herbert A. Simon

- ↑ ICGA Reference Database

- ↑ dblp: Herbert A. Simon

- ↑ Herbert Simon - Google Scholar Citations

- ↑ Bibliography of Herbert A. Simon -- 1930-1950's

- ↑ dblp: Herbert A. Simon

- ↑ General Problem Solver from Wikipedia

- ↑ Bibliography of Herbert A. Simon - 1960's

- ↑ Bibliography of Herbert A. Simon - 1970's

- ↑ The Human Intuition Project: Chase and Simon (1973) Perception in chess, Cognitive Psychology 4:55-81. A scientific blunder by Alexandre Linhares, October 01, 2007

- ↑ Physical symbol system from Wikipedia

- ↑ Bibliography of Herbert A. Simon - 1980's

- ↑ Bibliography of Herbert A. Simon - 1990's

- ↑ Dennis H. Holding (1992). Theories of Chess Skill. Psychological Research, Vol. 54, No. 1

- ↑ Bibliography of Herbert A. Simon - 2000-