El Ajedrecista

Home * Engines * El Ajedrecista

Home * History * El Ajedrecista

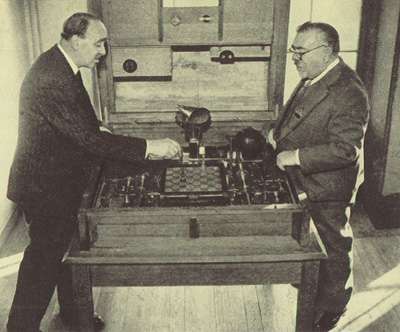

the electro-mechanical KRK solver by Leonardo Torres y Quevedo. In 1910 Torres began (other sources state 1890, or 1901 [2]) to construct the chess automaton. In 1912 it was able to automatically play a white king (initially on a8) and white rook (initially on b7) against the lonesome black king placed on any square, except 7th or 8th rank. The algorithm was suboptimal, but could win in less than 50 moves against any defense [3] . It used mechanical arms to make its moves and electrical sensors to detect its opponent's replies. A second, mechanical but not algorithmic improved El Ajedrecista was built by Leonardo Torres Quevedo's son Gonzalo in 1922, under the direction of his father. At the 1951 Paris Cybernetic Congress the advanced machine was introduced to a greater audience and explained to Norbert Wiener [4] . Even if only playing KRK, El Ajedrecista can be considered as the world’s first chess computer, even a dedicated robot able to move its own pieces. It is still functional and can be visited at the Torres Quevedo Museum of Engineering, Institute of Civil Engineering at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid [5]. During the WCCC 1992, hosted by the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, the original El Ajedrecista was an exhibit in the tournament hall [6].

Contents

Photos

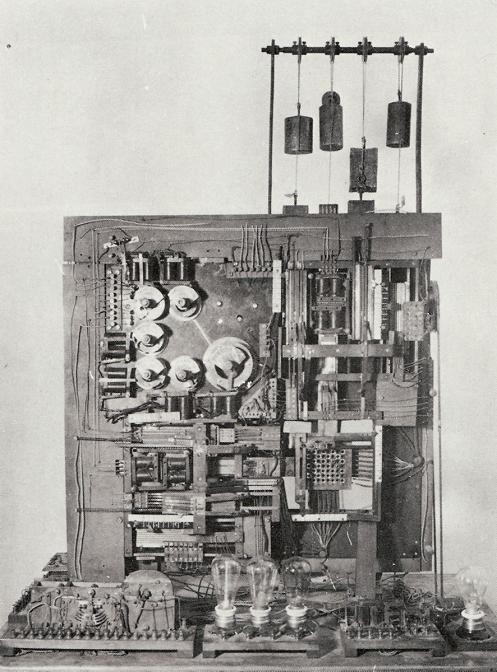

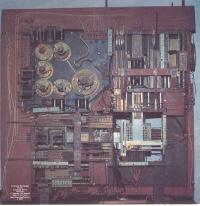

El Ajedrecista I

Front view of the 1911 chess playing automation. The chessboard is shown in the lower right of center. Horizontal and vertical arms moved the pieces (which were actually electrical jacks) from square to square, and the logic circuitry consisted of battery driven relays arranged in a logical tree structure [7] [8]

El Ajedrecista II

Gonzalo Torres y Quevedo and Norbert Wiener [9] [10]

Description

On March 17, 2007, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) recognized Torres’ Telekine [11] with an IEEE Milestone in Electrical Engineering and Computing [12] . The dedication was held at the Torres Quevedo Museum of Engineering, Institute of Civil Engineering, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, and following description of El Ajedrecista was given in the Celebration Ceremony Booklet Early Developments in Remote-Control, 1901 - The Telekine [13] [14] :

Roughly speaking, the movement of white pieces depends on the movement of the black king. Each of the 64 squares of the chess board (8 rows x 8 columns) are formed by three metallic pieces separated each other by an insulating material; the central piece is circular and is connected to the positive terminal whereas the side pieces are triangular and are respectively connected to two conductors, one horizontal and one vertical.

The black king has a silver mesh-base that connects the central piece of the square to the triangular ones, thus closing two electrical circuits that move two respective sliding bars, one horizontal and one vertical, until they reach two positions that determine the black king position on the chess board. Similarly, positions of the white king and rook are defined by four sliding bars, two for each of the pieces. When the black king moves into a position, the corresponding sliding bars move and close, by means of suitable contacts, the electrical circuits which act in turn on the white pieces making them move according to the game strategy. The white pieces have a steel ball in their base and are driven by electromagnets, which are placed under the table and suitably activated for each black king position.

When a check situation occurs, a phonographic disc pronounces the sentence “check to the king”. When checkmate occurs, the disc pronounces the corresponding sentence and a warning light indicating mate is turned on. In these cases, an electromagnet removes the tension from the board, thus ending the game. The automaton won. Although the chess automaton function was limited to particular chess endgames, Torres Quevedo proved that further advances in computer technology were possible at a time when the information about “artificial intelligence” was very limited. At the time of this invention Torres Quevedo was President of the Academy of Sciences of Madrid, Spain.

The Robot

A detailed explanation of El Ajedrecista can be found in Les Automates by Henri Vigneron [15] :

If the opponent plays an illegal move, a light comes on and the robot refuses to make a move. Once three such illegal moves have been made, the robot ceases to play altogether. If, on the contrary, the robot will carry out one of six operations, depending upon the position of the (just moved) black king. In order to archive this, Mr Torres use two zones on the chessboard: the one on the left consisting of the a-, b-, c-files, and the corresponding one on the right consisting of the h-, g-, and f-files (and a center zone consisting of d-, and e-file). We then have six operations as shown in the figure:

| The (defending) black King | |||||

| is in the same zone as the (white) rook |

is not in the same zone as the rook and the vertical distance between the black king and the rook is | ||||

| more than a square |

one square, with the vertical distance between the two kings being | ||||

| more than two squares |

two squares, with the number of square representing their horizontal distance apart being | ||||

| odd | even | zero | |||

| The rook moves away horizontally |

The rook moves down one square |

The king moves down one square |

The rook moves one square horizontally |

The white king moves one square towards the black king |

The rook moves down one square |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Assembly

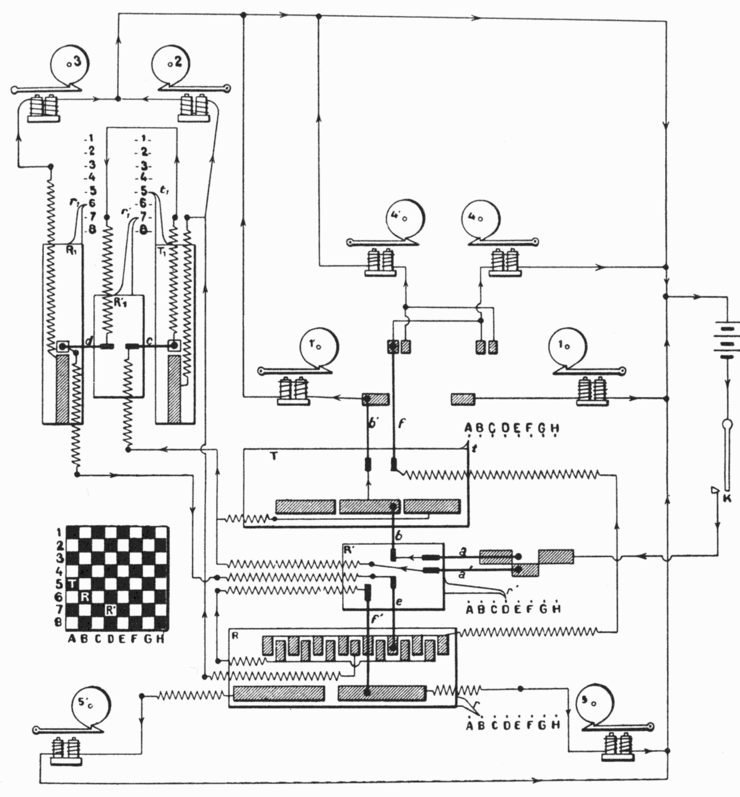

El Ajedrecista - principle assembly diagram [16]

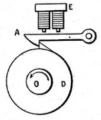

Making own Moves

Eight electro-mechanical actuators make the robot's own white king (left, right, down) or rook (left, right, down one square, horizontally to a- and h-file) moves and update its internal board representation. They are build using a disc (D) under friction torque of a spindle (O) driven by weights suspended from a cord wrapped around a pulley [17]. The disc has one sawtooth to prevent motion by an pawl unless an electromagnet (E) shortly attracts armature (A), allowing a full disc rotation, running a kind of mechanical microprogram for a specific piece movement. Using vertical and horizontal sliding arms, the robot addresses the origin square, grasps the piece from the board's plug hole, moves it over the target square to reinsert it into the board again.

and photo detail [18]

See also

Publications

- Henri Vigneron (1914). Les Automates. La Nature, pdf from cyberneticzoo.com, Translation by David Levy as Robots in David Levy, Monroe Newborn (1982). All About Chess and Computers. Springer, pp. 14-23, also in David Levy (ed.) (1988). Computer Chess Compendium, pp. 273-278.

- Anonymmous (1915). Torre and His Remarkable Automatic Devices. Scientific American, Supplement 80, Number 2079, November 06, 1915

- Donald Michie (1977). King and Rook Against King: Historical Background and a Problem on the Infinite Board. Advances in Computer Chess 1

- James M. Williams (1978). Antique Mechanical Computers, Part 3: The Torres Chess Automation. BYTE, Vol. 3, No. 9

- David Levy (1982). Robots. Translation of Henri Vigneron (1914). Les Automates. in David Levy, Monroe Newborn (1982). All About Chess and Computers. Springer, also in David Levy (ed.) (1988). Computer Chess Compendium, pp. 273-278. pdf from cyberneticzoo.com

- Brian Randell (1982). From Analytical Engine to Electronic Digital Computer: The Contributions of Ludgate, Torres, and Bush. Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 4, No. 4, October 1982, pdf [19] [20] [21]

- Ulrich Thiemonds (1999). Ein regelbasiertes Spielprogramm für Schachendspiele. University of Bonn, Diplom thesis, pdf, pp 34-36 "Historischer" Ansatz von Torres y Quevedo" (German)

Forum Posts

- "El Ajedristica" Programming Challenge by Ricardo Gibert, CCC, April 25, 2005

- One hundred years ago, the first chess computer by Steven Edwards, CCC, January 05, 2012

- Re: Programmer wanted to write chess game for an exhibition by Harm Geert Muller, CCC, November 04, 2012 (El Ajedrecista algorithm)

- chess-playing automaton , circa 1914 by Tom Glenn, CCC, February 10, 2014

External Links

- El Ajedrecista from Wikipedia

- El Ajedrecista from Wikipedia.es (Spanish)

- Universidad Politécnica de Madrid - Museo "Torres Quevedo"

- The first chess computer Chess Notes Archive by Edward Winter (note 4470, 4482)

- The first chess computer Chess Notes Archive by Edward Winter (note 4525, 4547)

- 1911 El Ajedrecista from Carolus Chess

- 1911-20 - Chess Playing Machines - Leonardo Torres y Quevedo from cyberneticzoo.com

- History of Computers and Computing, Automata, Leonardo Torres's chess-machine

- Cyber Heroes of the past: Leonardo Torres y Quevedo

- Mechanical Chess Opponent | Modern Mechanix

- Spain, September 6, 1955 - Leonardo Torres Quevedo: inventor of the first chess machine El Ajedrecista in 1911

- Imágenes del Autómata ajedrecista - Torres Quevedo (Spanish)

- Die Schachautomaten des Torres Quevedo by Hans-Peter Ketterling, Schachklub Tempelhof (German)

- Computer Schach by Andre Adrian, see Torres y Quevedo, Endspielautomat (German)

- The Rook Endgame Machine of Torres y Quevedo by Ramón Jiménez, ChessBase, July 20, 2004

- "El Ajedrecista" - an analog chess-playing computer from 1912, September 14, 2011 [22]

- Chess and the Automaton Endgame by Jon Turi, February 9th, 2014 [23]

- Leonardo Torres Quevedo Chess Automaton 1951, YouTube Video

References

- ↑ A New Photograph of “El jugador ajedrecista,” the World’s First Chess Computer by Nathan Bauman, July 16th, 2006

- ↑ The first chess computer Chess Notes Archive by Edward Winter (note 4525, 4547)

- ↑ David Levy in Computer Chess Compendium, Special Purpose Software and Hardware, pp. 266

- ↑ David Mindell, Jérôme Segal, Slava Gerovitch (2003). Cybernetics and Information Theory in the United States, France and the Soviet Union. in Mark Walker (ed.) (2003). Science and Ideology: A Comparative History. Routledge » Claude Shannon, Norbert Wiener, covers the 1951 Paris Cybernetic Congress

- ↑ Universidad Politécnica de Madrid - Museo "Torres Quevedo" (Spanish)

- ↑ Jaap van den Herik, Bob Herschberg (1992). The 7th World Computer-Chess Championship. Report on the Tournament. ICCA Journal, Vol. 15, No. 4

- ↑ Fotografía del primer ajedrecista. Del libro Obra e Inventos de Torres Quevedo. José García Santesmases. Editado en 1980 por el Instituto de España en la "Colección Cultura y Cienci, Imágenes del Autómata ajedrecista - Torres Quevedo (Spanish)

- ↑ James M. Williams (1978). Antique Mechanical Computers, Part 3: The Torres Chess Automation. BYTE, Vol. 3, No. 9

- ↑ A New Photograph of “El jugador ajedrecista,” the World’s First Chess Computer by Nathan Bauman, July 16th, 2006

- ↑ David Mindell, Jérôme Segal, Slava Gerovitch (2003). Cybernetics and Information Theory in the United States, France and the Soviet Union. in Mark Walker, Science and Ideology: A Comparative History » Claude Shannon, Norbert Wiener, covers the 1951 Paris Cybernetic Congress

- ↑ Antonio Pérez Yuste, Magdalena Salazar Palma (2004). The First Wireless Remote-Control: The Telekine of Torres Quevedo. pdf

- ↑ Cyber Heroes of the past: Leonardo Torres y Quevedo

- ↑ Torres-Quevedo Museum of Engineering - Early Developments in Remote-Control, 1901 - The Telekine (pdf, Spanish/English) Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos (Institute of Civil Engineering) - Universidad Politécnica de Madrid

- ↑ José Luis López Aranguren, Complutense University of Madrid

- ↑ Henri Vigneron (1914). Les Automates. La Nature, pdf from cyberneticzoo.com, Translation by David Levy as Robots in David Levy, Monroe Newborn (1982). All About Chess and Computers. Springer, pp. 14-23, also in David Levy (ed.) (1988). Computer Chess Compendium, pp. 273-278.

- ↑ Henri Vigneron (1914). Les Automates. La Nature, image pp. 61, pdf from cyberneticzoo.com

- ↑ Mechanical movements - Movement (clockwork) from Wikipedia

- ↑ Detail photos cropped from A New Photograph of “El jugador ajedrecista,” the World’s First Chess Computer by Nathan Bauman, July 16th, 2006

- ↑ Analytical Engine from Wikipedia

- ↑ Percy Ludgate from Wikipedia

- ↑ Vannevar Bush

- ↑ El Ajedrecista deals with discrete states and should not considered as analog computer

- ↑ chess-playing automaton , circa 1914 by Tom Glenn, CCC, February 10, 2014