Difference between revisions of "IBM 704"

GerdIsenberg (talk | contribs) (Created page with "'''Home * Hardware * IBM 704''' FILE:bernstein-alex.1958.l02645391.ibm-archives.jpg|border|right|thumb|link=http://www.computerhistory.org/chess/full_reco...") |

GerdIsenberg (talk | contribs) |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

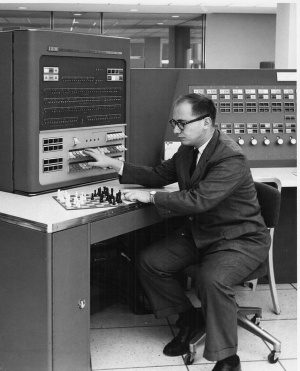

[[FILE:bernstein-alex.1958.l02645391.ibm-archives.jpg|border|right|thumb|link=http://www.computerhistory.org/chess/full_record.php?iid=stl-431614f6482e6| [[Alex Bernstein]], [[IBM 704]], 1958 <ref>[http://www.computerhistory.org/chess/full_record.php?iid=stl-431614f6482e6 IBM programmer Alex Bernstein] 1958 Courtesy of [[IBM]] Archives from [[The Computer History Museum]]</ref> ]] | [[FILE:bernstein-alex.1958.l02645391.ibm-archives.jpg|border|right|thumb|link=http://www.computerhistory.org/chess/full_record.php?iid=stl-431614f6482e6| [[Alex Bernstein]], [[IBM 704]], 1958 <ref>[http://www.computerhistory.org/chess/full_record.php?iid=stl-431614f6482e6 IBM programmer Alex Bernstein] 1958 Courtesy of [[IBM]] Archives from [[The Computer History Museum]]</ref> ]] | ||

| − | '''IBM 704''', | + | '''IBM 704''',<br/> |

| − | the first mass-produced computer, still with [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vacuum_tube vacuum tubes]. It used [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floating_point floating point] arithmetic hardware and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Core_memory Magnetic core memory], three [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Index_register index registers], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/36-bit 36-bit] [[Word|words]]. The IBM 704 was able to process about 40,000 instructions per second, and was introduced in 1954. The instruction format was 3-bit prefix, 15-bit decrement, 3-bit tag, and 15-bit address. The prefix field specified the class of instruction, the decrement field often contained an immediate operand, or was used to further define the instruction type. The tag bits specified any combination of three index registers, in which the contents of the registers were subtracted from the address to produce an effective address of an memory operand. The programming languages [[Fortran]] and [[ | + | the first mass-produced computer, still with [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vacuum_tube vacuum tubes]. It used [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floating_point floating point] arithmetic hardware and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Core_memory Magnetic core memory], three [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Index_register index registers], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/36-bit 36-bit] [[Word|words]]. The IBM 704 was able to process about 40,000 instructions per second, and was introduced in 1954. The instruction format was 3-bit prefix, 15-bit decrement, 3-bit tag, and 15-bit address. The prefix field specified the class of instruction, the decrement field often contained an immediate operand, or was used to further define the instruction type. The tag bits specified any combination of three index registers, in which the contents of the registers were subtracted from the address to produce an effective address of an memory operand. The programming languages [[Fortran]] and [[LISP]] were first developed for the 704. In 1957 [[Alex Bernstein]] et al. wrote the first complete chess program for the IBM 704, [[The Bernstein Chess Program]]. |

| + | |||

| + | =<span id="QuoteMachinesWhoThink"></span>Quotes= | ||

| + | from ''[[Artificial Intelligence#MachinesWhoThink|Machines Who Think]]'' <ref>[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pamela_McCorduck Pamela McCorduck] ('''2004'''). ''[[Artificial Intelligence#MachinesWhoThink|Machines Who Think: A Personal Inquiry into the History and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence]]''. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_K_Peters A. K. Peters] (25th anniversary edition)</ref> <ref>[https://www.gettyimages.de/fotos/ibm-704?editorialproducts=timelife&family=editorial&phrase=IBM%20704&page=1&recency=anydate&suppressfamilycorrection=true Photos] with [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lasker Edward Lasker] by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andreas_Feininger Andreas Feininger], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Getty_Images Getty Images]</ref>: | ||

| + | [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Life_(magazine) Life magazine] came asking for photographs of [[Alex Bernstein|Bernstein]] sitting at the computer, and wondered if they could get [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bobby_Fischer Bobby Fischer] to pose too. He was in his early teens at the time, but shrewd enough, and said he would for a fee of $2500, Bernstein recalls: | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''They said forget it, and asked me did I know anyone else who might be willing to pose for a picture. And I said, I’m sure that [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lasker Ed Lasker] was a very respected name in chess and a charming man and a gentleman, and would not ask for $2500. He said he would be delighted, and they paid us each $1. The funny thing about it is they proceeded to go to some antique dealer on [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madison_Avenue Madison Avenue] and rented a chess set — an Indian chess set of the sixteenth century which cost all of $2500 and a chess board which cost $1200, and everybody was absolutely dying in case any of the pieces should fall over. They were extremely delicate filigree ivory, and they were insured''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But the pictures didn’t turn out and had to be retaken, meaning that the chess set and board had to be re-rented, the cost well exceeding, Bernstein calculates, what it would have cost to rent Bobby Fischer instead. As it turned out, Life never did use the pictures in its magazine, although six or seven years later Bernstein was surprised to discover a picture of himself and Ed Lasker standing in front of their 704 in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time_Life Time-Life] series on mathematics. But [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_J._Watson T. J. Watson], the president of [[IBM]], was not amused. IBM’s original, or at least official, justification for allowing Bernstein to use the first 704 for nothing more serious than game playing had been the hope that if he were successful, it would show the world — in particular, business people — that computers could be used to solve problems even as difficult as ones that came up in business. But IBM’s stockholders had challenged Watson at the last meeting, wanting an explanation for the money being wasted on playing games. | ||

=Chess Programs= | =Chess Programs= | ||

| Line 14: | Line 22: | ||

=Selected Publications= | =Selected Publications= | ||

| + | * [[Nathaniel Rochester]], [[Mathematician#Holland|John H. Holland]], [https://dblp.uni-trier.de/pers/hd/h/Haibt:L=_H= L. H. Haibt], [https://dblp.uni-trier.de/pers/hd/d/Duda:William_L= William L. Duda] ('''1956'''). ''[https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Tests-on-a-cell-assembly-theory-of-the-action-of-a-Rochester-Holland/878d615b84cf779e162f62c4a9192d6bddeefbf9 Tests on a Cell Assembly Theory of the Action of the Brain, Using a Large Digital Computer]''. [https://dblp.uni-trier.de/db/journals/tit/tit2n.html IRE Transactions on Information Theory, Vol. 2], No. 3 | ||

* [[Alex Bernstein]], [[Michael de V. Roberts]], [[Timothy Arbuckle]], [[Martin Belsky]] ('''1958'''). ''[http://www.computerhistory.org/chess/full_record.php?iid=doc-431e18a41d415 A chess playing program for the IBM 704]''. Proceedings of the 1958 Western Joint Computer Conference, [http://archive.computerhistory.org/projects/chess/related_materials/text/2-2.A_Chess_Playing_Program_for_the_IBM_704.Bernstein_Roberts_Arbuckle_Belsky/A_Chess_Playing_Program_for_the_IBM_704.Bernstein_Roberts_Arbuckle_Belsky.062303011.pdf pdf] | * [[Alex Bernstein]], [[Michael de V. Roberts]], [[Timothy Arbuckle]], [[Martin Belsky]] ('''1958'''). ''[http://www.computerhistory.org/chess/full_record.php?iid=doc-431e18a41d415 A chess playing program for the IBM 704]''. Proceedings of the 1958 Western Joint Computer Conference, [http://archive.computerhistory.org/projects/chess/related_materials/text/2-2.A_Chess_Playing_Program_for_the_IBM_704.Bernstein_Roberts_Arbuckle_Belsky/A_Chess_Playing_Program_for_the_IBM_704.Bernstein_Roberts_Arbuckle_Belsky.062303011.pdf pdf] | ||

* [[John McCarthy]] ('''1960'''). ''Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I'', [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology]], [http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/recursive.pdf pdf] | * [[John McCarthy]] ('''1960'''). ''Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I'', [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology]], [http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/recursive.pdf pdf] | ||

| + | * [https://dblp.uni-trier.de/pers/b/Bashe:Charles_J=.html Charles J. Bashe], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Werner_Buchholz Werner Buchholz], [https://dblp.uni-trier.de/pers/h/Hawkins:George_V=.html George V. Hawkins], [https://dblp.uni-trier.de/pers/hd/i/Ingram:J=_James J. James Ingram], [[Nathaniel Rochester]] ('''1981'''). ''[https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1147/rd.255.0363 The Architecture of IBM's Early Computers]''. [http://www.dblp.org/db/journals/ibmrd/ibmrd25.html#BasheBHIR81 IBM Journal of Research and Development, Vol. 25, No. 5], [https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/58e7/9f00e2e012ac64de130982fc3b991284a50a.pdf pdf] | ||

=External Links= | =External Links= | ||

| Line 22: | Line 32: | ||

* [http://www.columbia.edu/acis/history/704.html The IBM 704] by [http://www.columbia.edu/~fdc/ Frank da Cruz], [[Columbia University]] | * [http://www.columbia.edu/acis/history/704.html The IBM 704] by [http://www.columbia.edu/~fdc/ Frank da Cruz], [[Columbia University]] | ||

* [http://www.quadibloc.com/comp/cp0309.htm From the IBM 704 to the IBM 7094] by [http://www.quadibloc.com/ John J. G. Savard] | * [http://www.quadibloc.com/comp/cp0309.htm From the IBM 704 to the IBM 7094] by [http://www.quadibloc.com/ John J. G. Savard] | ||

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.gettyimages.de/fotos/ibm-704?editorialproducts=timelife&family=editorial&phrase=IBM%20704&page=1&recency=anydate&suppressfamilycorrection=true Photos] with [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lasker Edward Lasker] by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andreas_Feininger Andreas Feininger], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Getty_Images Getty Images] » [[#QuoteMachinesWhoThink|Quote from Machines Who Think]] |

=References= | =References= | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

| − | |||

'''[[Hardware|Up one Level]]''' | '''[[Hardware|Up one Level]]''' | ||

| + | [[Category:Quotes]] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:14, 23 July 2020

IBM 704,

the first mass-produced computer, still with vacuum tubes. It used floating point arithmetic hardware and Magnetic core memory, three index registers, 36-bit words. The IBM 704 was able to process about 40,000 instructions per second, and was introduced in 1954. The instruction format was 3-bit prefix, 15-bit decrement, 3-bit tag, and 15-bit address. The prefix field specified the class of instruction, the decrement field often contained an immediate operand, or was used to further define the instruction type. The tag bits specified any combination of three index registers, in which the contents of the registers were subtracted from the address to produce an effective address of an memory operand. The programming languages Fortran and LISP were first developed for the 704. In 1957 Alex Bernstein et al. wrote the first complete chess program for the IBM 704, The Bernstein Chess Program.

Quotes

from Machines Who Think [2] [3]:

Life magazine came asking for photographs of Bernstein sitting at the computer, and wondered if they could get Bobby Fischer to pose too. He was in his early teens at the time, but shrewd enough, and said he would for a fee of $2500, Bernstein recalls:

They said forget it, and asked me did I know anyone else who might be willing to pose for a picture. And I said, I’m sure that Ed Lasker was a very respected name in chess and a charming man and a gentleman, and would not ask for $2500. He said he would be delighted, and they paid us each $1. The funny thing about it is they proceeded to go to some antique dealer on Madison Avenue and rented a chess set — an Indian chess set of the sixteenth century which cost all of $2500 and a chess board which cost $1200, and everybody was absolutely dying in case any of the pieces should fall over. They were extremely delicate filigree ivory, and they were insured.

But the pictures didn’t turn out and had to be retaken, meaning that the chess set and board had to be re-rented, the cost well exceeding, Bernstein calculates, what it would have cost to rent Bobby Fischer instead. As it turned out, Life never did use the pictures in its magazine, although six or seven years later Bernstein was surprised to discover a picture of himself and Ed Lasker standing in front of their 704 in the Time-Life series on mathematics. But T. J. Watson, the president of IBM, was not amused. IBM’s original, or at least official, justification for allowing Bernstein to use the first 704 for nothing more serious than game playing had been the hope that if he were successful, it would show the world — in particular, business people — that computers could be used to solve problems even as difficult as ones that came up in business. But IBM’s stockholders had challenged Watson at the last meeting, wanting an explanation for the money being wasted on playing games.

Chess Programs

See also

Selected Publications

- Nathaniel Rochester, John H. Holland, L. H. Haibt, William L. Duda (1956). Tests on a Cell Assembly Theory of the Action of the Brain, Using a Large Digital Computer. IRE Transactions on Information Theory, Vol. 2, No. 3

- Alex Bernstein, Michael de V. Roberts, Timothy Arbuckle, Martin Belsky (1958). A chess playing program for the IBM 704. Proceedings of the 1958 Western Joint Computer Conference, pdf

- John McCarthy (1960). Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, pdf

- Charles J. Bashe, Werner Buchholz, George V. Hawkins, J. James Ingram, Nathaniel Rochester (1981). The Architecture of IBM's Early Computers. IBM Journal of Research and Development, Vol. 25, No. 5, pdf

External Links

- IBM 704 from Wikipedia

- IBM Archives: Photo Album: 704 Data Processing System

- The IBM 704 by Frank da Cruz, Columbia University

- From the IBM 704 to the IBM 7094 by John J. G. Savard

- Photos with Edward Lasker by Andreas Feininger, Getty Images » Quote from Machines Who Think

References

- ↑ IBM programmer Alex Bernstein 1958 Courtesy of IBM Archives from The Computer History Museum

- ↑ Pamela McCorduck (2004). Machines Who Think: A Personal Inquiry into the History and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence. A. K. Peters (25th anniversary edition)

- ↑ Photos with Edward Lasker by Andreas Feininger, Getty Images